Raccontare il cambiamento climatico

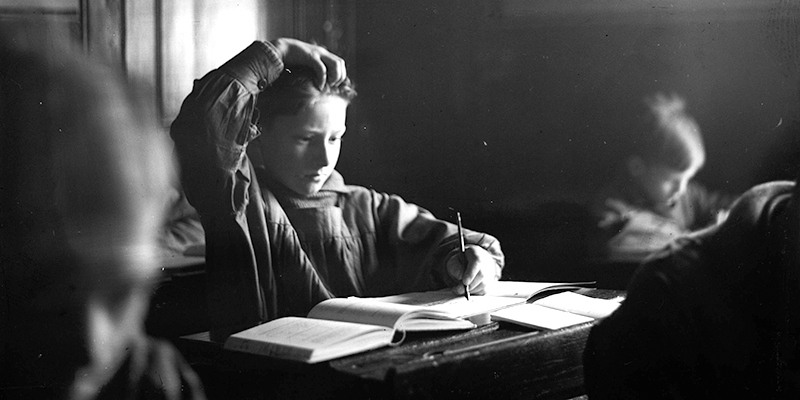

Cosa succede quando le persone sono costrette a migrare a causa di disastri ambientali e cambiamenti del clima, raccontato con le fotografie di Alessandro Grassani

di Sarah Carlet

altre

foto

Alessandro Grassani è un fotografo italiano nato a Pavia nel 1977. Dopo aver studiato fotografia all’istituto Bauer di Milano e aver lavorato con la fotografia commerciale, ha deciso di dedicarsi ai reportage raccontado storie da più di 30 paesi nel mondo. Un suo progetto molto interessante si intitola Environmental migrant: The last illusion, un lavoro molto complesso che Grassani porta in giro da qualche tempo e che è stato esposto l’anno scorso al festival di fotografia Cortona On The Move.

Alessandro Grassani documenta la relazione tra uomo e ambiente e cosa succede quando certi eventi catastrofici, certi atteggiamenti, determinate condizioni portano alcune persone a migrare proprio a causa del mutamento delle condizioni climatiche.

Il progetto è articolato in tre tappe: Ulan Bator in Mongolia, Dhaka in Bangladesh, Nairobi in Kenya. Grassani prova a rappresentare una gamma di cambiamenti climatici e rischi naturali che influenzano il fenomeno delle migrazioni verso le città (il 2008 ha segnato il punto di non ritorno: per la prima volta nella storia dell’uomo la gente che vive nelle città ha superato quella delle campagne).

Alessandro Grassani si autofinanzia e per portare avanti il suo lavoro si affida al crowdfunding, raccogliendo soldi online. Così è stata possibile la sua ultima tappa, il Kenya. Grassani racconta:

“Si tratta di gente comune, privati cittadini che credono e desiderano vedere realizzati idee e progetti. Nel mio caso in cambio ricevono una ricompensa, come una foto o il nome incluso nella pagina dei ringraziamenti. Negli ultimi anni la fotografia è in crisi e si fa molta fatica a finanziare progetti costosi. Questa è stata la mia prima esprienza con il crowdfunding. Mi ha emozionato vedere il fermento che si è creato intorno al progetto e soprattutto avere avuto la possibilità di entrare in relazione con persone completamente sconosciute a cui mostrare il lavoro.”

Tra settembre e ottobre prossimi, Grassani andrà in Kenya proprio durante la stagione secca, per completare il suo viaggio. È possibile seguirlo durante la sua ricerca attraverso il suo sito, la sua pagina Facebook e Twitter.